Frank Gehry’s 12 Most Iconic Buildings

06.12.2025

Frank Gehry: A Singular Visionary and His Landmark Works

Frank Gehry, who died Friday at 96, was widely regarded as the most influential architect of his generation — a sharp-witted, restless, often divisive visionary who reshaped what buildings could be. With exuberant creations like Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles and the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, he upended conventional notions of form and materials, and in the process became such a cultural figure that he even appeared as a character on “The Simpsons.”

From Bilbao and Berlin to New York and, above all, Los Angeles — the city with which he became deeply intertwined — Gehry left behind a portfolio of audacious, sometimes controversial, yet technically and artistically groundbreaking work. His architecture mirrors the broader trajectory of postwar American culture: experimental, disruptive, and increasingly media-savvy.

Some of his most interesting buildings are not necessarily the most famous: early, small-scale experiments with limited budgets, and late-career designs for unrealized projects and concert halls that reveal his abiding love of music. Below is a curated selection of 12 essential Gehry works and ideas.

Early Experiments and Residential Icons

Danziger House, Los Angeles (1964–65)

Hidden among the noisy bars along Melrose Avenue, the Danziger house and studio marked Gehry’s arrival on Los Angeles’s architectural scene. Completed in 1965, the project consists of two restrained gray stucco volumes recessed from the street, their mostly blank facades sheltering a more private interior courtyard.

Large windows and skylights draw sunlight into the cube-like forms, carving dramatic shadows within. Even here, Gehry is already elevating the ordinary: exposed conduits and ventilation recall SoHo lofts, and the stucco is the same utilitarian material sprayed on freeway underpasses — a pragmatic choice turned into poetic architecture.

Ron Davis House, Malibu, California (1968–72)

Gehry’s collaboration with painter Ron Davis, a hard-edge abstractionist known for his shaped canvases, led to one of the architect’s first nationally recognized projects. The Malibu home and studio took the form of a sharply angled trapezoid that echoed Davis’s art.

Constructed with plywood and corrugated metal, the house extended Gehry’s interest in unconventional geometries and what he jokingly termed “cheapskate” materials. Though Davis sold the property in 2003, the house itself was tragically destroyed in a 2018 fire.

Frank and Berta Gehry Residence, Santa Monica, California (1977–92)

What began as an unremarkable pink Dutch Colonial bungalow from the 1920s became Gehry’s personal laboratory — and one of his most influential works. When he and his wife, Berta, bought the house in Santa Monica, he set about encasing, dissecting, and extending it with raw materials like chain-link fencing, plywood and corrugated metal.

The result horrified some neighbors but thrilled architects and design enthusiasts. The house became a touchstone of late 20th-century residential design, drawing inspiration from artists such as Marcel Duchamp and Gordon Matta-Clark, and rewriting expectations of what a home could look like.

International Breakthroughs

Vitra Design Museum and Factory, Weil am Rhein, Germany (completed 1989)

Gehry’s first completed European project, for the Swiss furniture company Vitra, marked a major turning point in his career. The ensemble of museum and warehouse layers swooping, angular, and jutting forms into a sculptural whole that also responds to specific programmatic needs.

The building nods to earlier masters — Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim in New York, and perhaps Le Corbusier’s chapel at Ronchamp — while pointing toward a new architectural language. The project became strongly associated with Deconstructivism, a movement characterized by fractured geometries and complex, computer-assisted forms that felt perfectly suited to an era dominated by photography and emerging digital media.

“Fred and Ginger,” Prague, Czech Republic (1992–96)

On a site left empty since World War II bombing, Gehry created one of his most playful designs: a pair of office towers that appear to dance together. Nicknamed “Fred and Ginger” after the Hollywood dance duo, the buildings contrast whimsical curves with references to Prague’s historic 19th-century architecture.

Completed shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the project captured a spirit of newfound openness and optimism in Central Europe. The leaning, twisting forms step away from their more conventional neighbors, much as the city itself was stepping out from the shadow of Soviet rule.

Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, Spain (1991–97)

Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao — often likened to a giant, shimmering fish on the riverfront — transformed not just a city but the perception of contemporary architecture. The museum helped turn the former industrial port into an international destination to rival Rome or Paris for art and architecture lovers.

Bilbao offered Gehry an unusually supportive client, giving him room to push structural and technological limits. The result was so extraordinary that architect Philip Johnson compared it to Chartres Cathedral. Whether or not it stands for 800 years, it is the building that will always be most closely tied to Gehry’s name and to architecture’s late 20th-century turning point.

Defining the Skyline

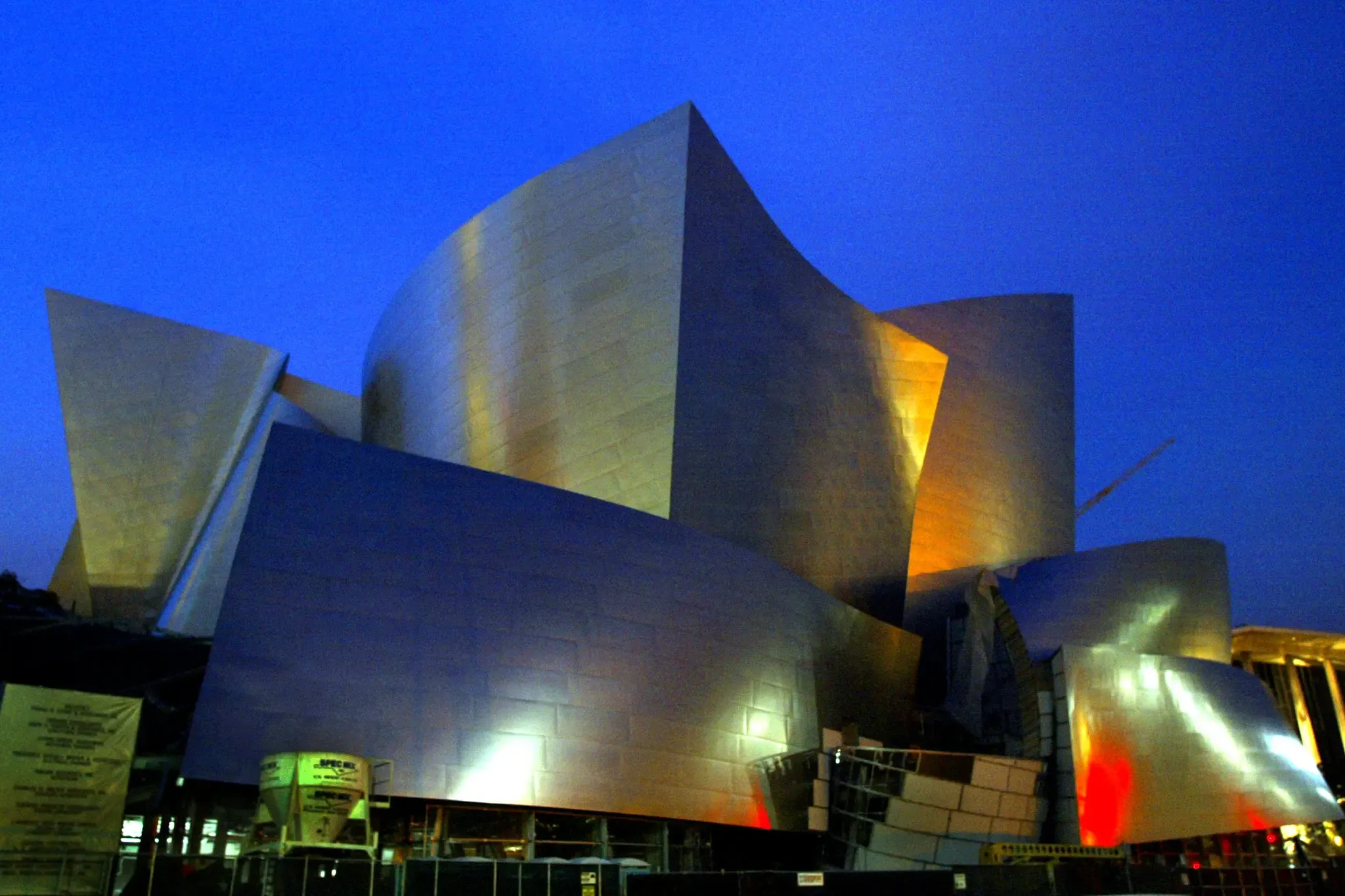

Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles (1988–2003)

Walt Disney Concert Hall is both an acoustical triumph and a monumental sculpture in the city. Inside, the warm, wood-clad auditorium is celebrated as one of the world’s great places to experience live music. Outside, a cascade of stainless-steel panels opens up like petals under the Southern California sun.

For downtown Los Angeles, Disney Hall became what the Chrysler Building is for New York or the Eiffel Tower is for Paris: an instant emblem. Conceived before but completed after Bilbao, it also fed into Gehry’s thinking for the Spanish museum and now ranks alongside it as one of his greatest achievements.

DZ Bank, Berlin (completed 2001)

Near Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate, Gehry slipped a surprising, almost surreal interior into an otherwise restrained mixed-use building. At the heart of the project is a conference hall that seems to hover in space, its undulating form likened by some to a whale floating in midair.

From the outside, the building appears almost conventional, making the dramatic interior feel like a punchline revealed only once you step inside. It’s an architectural tour de force echoing, in its own way, what Norman Foster achieved at the nearby Reichstag — a sober exterior concealing a powerful, symbolic interior gesture.

8 Spruce Street, New York City (completed 2011)

Gehry’s first skyscraper, 8 Spruce Street in Lower Manhattan, rises 76 stories and is wrapped in over 10,000 uniquely shaped stainless steel panels. The rippling facade suggests fabric caught in motion, with folds that create bay windows protruding like ship prows from the high-end apartments.

The tower subtly acknowledges the nearby Woolworth Building with its neo-Gothic ornament and reflective terra-cotta. Over the course of the day, the building’s metallic cladding appears to “breathe,” shifting from pinkish hues at dawn to deeper umber tones as the sun sets.

Sculpting Light and Sound

Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris (completed 2014)

At the edge of the Bois de Boulogne in Paris, Gehry traded metal for sweeping glass sails in one of his most lyrical works. The Louis Vuitton Foundation’s overlapping glass volumes evoke different images: a sailing ship, breaking icebergs, or the facets of a Cubist collage.

The building recalls earlier Parisian glass structures like the Grand Palais while advancing Gehry’s own exploration of expressive forms. Inside, gallery spaces alternate between straightforward rectangular rooms and more sculptural, complex volumes. For Gehry, the idea that “neutral” white boxes are somehow invisible was a myth; perfectly controlled gallery spaces, he argued, confront art just as forcefully as more expressive ones.

Pierre Boulez Saal, Berlin (completed 2017)

In his later years, Gehry dedicated increasing energy to concert halls, reflecting his lifelong passion for music. Pierre Boulez Saal, created in collaboration with conductor and pianist Daniel Barenboim, is an intimate 683-seat venue that feels almost like a musical instrument itself.

Set inside a historic masonry building, the hall features curving wooden tiers of seating that encircle the stage, creating a warm, enveloping acoustic environment. Named for the modernist composer Pierre Boulez, the space shows Gehry as an intimist rather than a showman — an architect capable of designing modest, humane rooms that recede so that music and people can take center stage.

A Vision for Los Angeles’s Future (Unbuilt)

Los Angeles River Proposal

Despite his international acclaim, Gehry remained deeply tied to Los Angeles, the city where he lived and worked for decades. His office continued to take on local projects, including supportive housing for formerly homeless veterans and a visionary plan to reimagine a neglected section of the Los Angeles River.

The river proposal, never realized, envisioned a roughly mile-long platform built over the existing concrete channel. It would have introduced new parkland, public spaces and a cultural center in some of the city’s most underserved neighborhoods, demonstrating Gehry’s interest not only in iconic buildings but in urban repair and social impact.

Together, these 12 projects and proposals show the full range of Gehry’s work — from modest early experiments and radical home renovations to global landmarks and unbuilt dreams — and make clear why he remains one of the defining architects of our time.